In this article we will discuss about:- 1. Fisher’s Equation of Exchange 2. Assumptions of Fisher’s Quantity Theory 3. Conclusions 4. Criticisms 5. Merits 6. Implications 7. Examples.

- An Assumption Of The Quantity Theory Of Money Is That Real Gdp Growth

- Quantity Theory Of Money Equation

- Simple Quantity Theory Of Money

- The Quantity Theory Of Money Assumes That Real Gdp Is Defined

- Quantity Theory Of Money Definition

- Quantity Theory Of Money Assumptions

Fisher’s Equation of Exchange:

The quantity theory of money emphasizes that the money supply is the main determinant of nominal GDP. The quantity theory of money is explained by referring to the equation of exchange.

- Since quantity theory of money uses money stock to explain income flow, the theoretical framework of quantity theory of money is false. Since M2 grew slow after 2008, slow recovery after 2009 was explained by the close correlation between money supply and GDP.

- Quantity Theory of Money— Fisher’s Version: Like the price of a commodity, value of money is determinded by the supply of money and demand for money. In his theory of demand for money, Fisher attached emphasis on the use of money as a medium of exchange. In other words, money is demanded for transaction purposes.

The transactions version of the quantity theory of money was provided by the American economist Irving Fisher in his book- The Purchasing Power of Money (1911). According to Fisher, “Other things remaining unchanged, as the quantity of money in circulation increases, the price level also increases in direct proportion and the value of money decreases and vice versa”.

Fisher’s quantity theory is best explained with the help of his famous equation of exchange:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

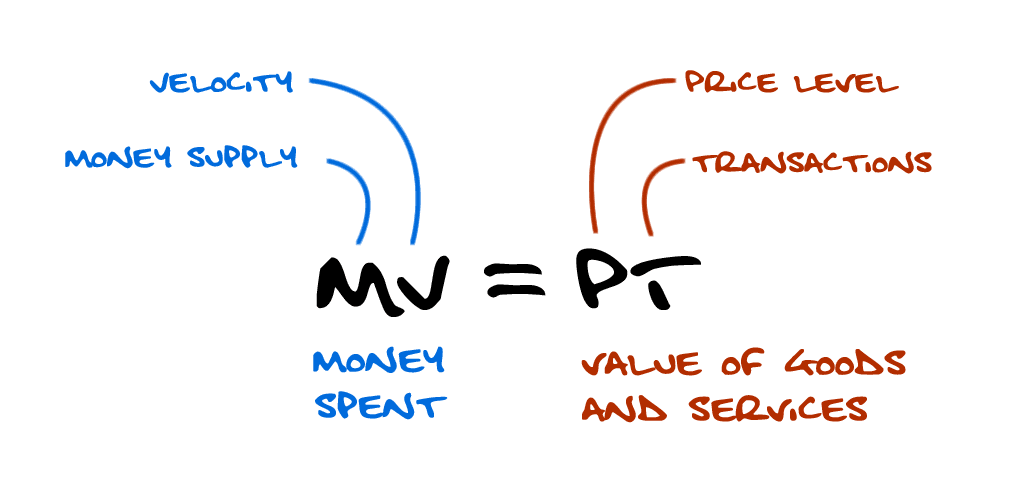

MV = PT or P = MV/T

Like other commodities, the value of money or the price level is also determined by the demand and supply of money.

i. Supply of Money:

The supply of money consists of the quantity of money in existence (M) multiplied by the number of times this money changes hands, i.e., the velocity of money (V). In Fisher’s equation, V is the transactions velocity of money which means the average number of times a unit of money turns over or changes hands to effectuate transactions during a period of time.

Thus, MV refers to the total volume of money in circulation during a period of time. Since money is only to be used for transaction purposes, total supply of money also forms the total value of money expenditures in all transactions in the economy during a period of time.

ii. Demand for Money:

Money is demanded not for its own sake (i.e., for hoarding it), but for transaction purposes. The demand for money is equal to the total market value of all goods and services transacted. It is obtained by multiplying total amount of things (T) by average price level (P).

Thus, Fisher’s equation of exchange represents equality between the supply of money or the total value of money expenditures in all transactions and the demand for money or the total value of all items transacted.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Supply of money = Demand for Money

Or

Total value of money expenditures in all transactions = Total value of all items transacted

MV = PT

or

P = MV/T

Where,

M is the quantity of money

V is the transaction velocity

ADVERTISEMENTS:

P is the price level.

T is the total goods and services transacted.

The equation of exchange is an identity equation, i.e., MV is identically equal to PT (or MV = PT). It means that in the ex-post or factual sense, the equation must always be true. The equation states the fact that the actual total value of all money expenditures (MV) always equals the actual total value of all items sold (PT).

What is spent for purchases (MV) and what is received for sale (PT) are always equal; what someone spends must be received by someone. In this sense, the equation of exchange is not a theory but rather a truism.

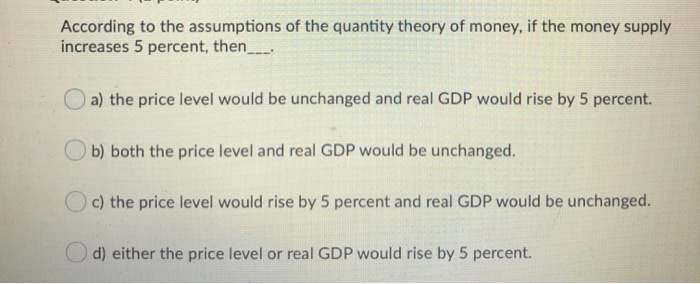

Irving Fisher used the equation of exchange to develop the classical quantity theory of money, i.e., a causal relationship between the money supply and the price level. On the assumptions that, in the long run, under full-employment conditions, total output (T) does not change and the transactions velocity of money (V) is stable, Fisher was able to demonstrate a causal relationship between money supply and price level.

In this way, Fisher concludes, “… the level of price varies directly with the quantity of money in circulation provided the velocity of circulation of that money and the volume of trade which it is obliged to perform are not changed”. Thus, the classical quantity theory of money states that V and T being unchanged, changes in money cause direct and proportional changes in the price level.

Irving Fisher further extended the equation of exchange so as to include demand (bank) deposits (M’) and their velocity, (V’) in the total supply of money.

Thus, the equation of exchange becomes:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, according to Fisher, the level of general prices (P) depends exclusively on five definite factors:

(a) The volume of money in circulation (M);

(b) Its velocity of circulation (V) ;

(c) The volume of bank deposits (M’);

(d) Its velocity of circulation (V’); and

(e) The volume of trade (T).

An Assumption Of The Quantity Theory Of Money Is That Real Gdp Growth

The transactions approach to the quantity theory of money maintains that, other things remaining the same, i.e., if V, M’, V’, and T remain unchanged, there exists a direct and proportional relation between M and P; if the quantity of money is doubled, the price level will also be doubled and the value of money halved; if the quantity of money is halved, the price level will also be halved and the value of money doubled.

Example:

Fisher’s quantity theory of money can be explained with the help of an example. Suppose M = Rs. 1000. M’ = Rs. 500, V = 3, V’ = 2, T = 4000 goods.

Thus, when money supply in doubled, i.e., increases from Rs. 4000 to 8000, the price level is doubled. i.e., from Re. 1 per good to Rs. 2 per good and the value of money is halved, i.e., from 1 to 1/2.

Thus, when money supply is halved, i.e., decreases from Rs. 4000 to 2000, the price level is halved, i.e., from 1 to 1/2, and the value of money is doubled, i.e., from 1 to 2.

The effects of a change in money supply on the price level and the value of money are graphically shown in Figure 1-A and B respectively:

(i) In Figure 1-A, when the money supply is doubled from OM to OM1, the price level is also doubled from OP to OP1. When the money supply is halved from OM to OM2, the price level is halved from OP to OP2. Price curve, P = f(M), is a 45° line showing a direct proportional relationship between the money supply and the price level.

(ii) In Figure 1-B, when the money supply is doubled from OM to OM1; the value of money is halved from O1/P to O1/P1 and when the money supply is halved from OM to OM2, the value of money is doubled from O1/P to O1/P2. The value of money curve, 1/P = f (M) is a rectangular hyperbola curve showing an inverse proportional relationship between the money supply and the value of money.

Assumptions of Fisher’s Quantity Theory:

Fisher’s transactions approach to the quantity theory of money is based on the following assumptions:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

1. Constant Velocity of Money:

According to Fisher, the velocity of money (V) is constant and is not influenced by the changes in the quantity of money. The velocity of money depends upon exogenous factors like population, trade activities, habits of the people, interest rate, etc. These factors are relatively stable and change very slowly over time. Thus, V tends to remain constant so that any change in supply of money (M) will have no effect on the velocity of money (V).

2. Constant Volume of Trade or Transactions:

Total volume of trade or transactions (T) is also assumed to be constant and is not affected by changes in the quantity of money. T is viewed as independently determined by factors like natural resources, technological development, population, etc., which are outside the equation and change slowly over time. Thus, any change in the supply of money (M) will have no effect on T. Constancy of T also means full employment of resources in the economy.

3. Price Level is a Passive Factor:

According to Fisher the price level (P) is a passive factor which means that the price level is affected by other factors of equation, but it does not affect them. P is the effect and not the cause in Fisher’s equation. An increase in M and V will raise the price level. Similarly, an increase in T will reduce the price level.

4. Money is a Medium of Exchange:

The quantity theory of money assumed money only as a medium of exchange. Money facilitates the transactions. It is not hoarded or held for speculative purposes.

5. Constant Relation between M and M’:

Fisher assumes a proportional relationship between currency money (M) and bank money (M’). Bank money depends upon the credit creation by the commercial banks which, in turn, are a function of the currency money (M). Thus, the ratio of M’ to M remains constant and the inclusion of M’ in the equation does not disturb the quantitative relation between quantity of money (M) and the price level (P).

6. Long Period:

The theory is based on the assumption of long period. Over a long period of time, V and T are considered constant.

Thus, when M’, V, V’ and T in the equation MV + M’Y’ = PT are constant over time and P is a passive factor, it becomes clear, that a change in the money supply (M) will lead to a direct and proportionate change in the price level (P).

Broad Conclusions of Fisher’s Quantity Theory:

(i) The general price level in a country is determined by the supply of and the demand for money.

(ii) Given the demand for money, changes in money supply lead to proportional changes in the price level.

(iii) Since money is only a medium of exchange, changes in the money supply change absolute (nominal), and not relative (real), prices and thus leave the real variables such as employment and output unaltered. Money is neutral.

(iv) Under the equilibrium conditions of full employment, the role of monetary (or fiscal) policy is limited.

(v) During the temporary disequilibrium period of adjustment, an appropriate monetary policy can stabilise the economy.

(vi) The monetary authorities, by changing the supply of money, can influence and control the price level and the level of economic activity of the country.

Criticisms of Quantity Theory of Money:

The quantity theory of money as developed by Fisher has been criticised on the following grounds:

1. Interdependence of Variables:

The various variables in transactions equation are not independent as assumed by the quantity theorists:

(i) M Influences V – As money supply increases, the prices will increase. Fearing further rise in price in future, people increase their purchases of goods and services. Thus, velocity of money (V) increases with the increase in the money supply (M).

(ii) M Influences V’ – When money supply (M) increases, the velocity of credit money (V’) also increases. As prices increase because of an increase in money supply, the use of credit money also increases. This increases the velocity of credit money (V’).

(iii) P Influences T – Fisher assumes price level (P) as a passive factor having no effect on trade (T). But, in reality, rising prices increase profits and thus promote business and trade.

(iv) P Influences M – According to the quantity theory of money, changes in money supply (M) is the cause and changes in the price level (P) is the effect. But, critics maintain that a change in the price level occurs independently and this later on influences money supply.

(v) T Influences V – If there is an increase in the volume of trade (T), it will definitely increase the velocity of money (V).

(vi) T Influences M – During prosperity growing volume of trade (T) may lead to an increase in the money supply (M), without altering the prices.

(vii) M and T are not Independent – According to Keynes, output remains constant only under the condition of full employment. But, in reality less-than-full employment prevails and an increase in the money supply increases output (T) and employment.

2. Unrealistic Assumption of Long Period:

The quantity theory of money has been criticised on the ground that it provides a long-term analysis of value of money. It throws no light on the short-run problems. Keynes has aptly remarked that “in the long-run we are all dead”. Actual problems are short-run problems. Thus, quantity theory has no practical value.

3. Unrealistic Assumption of full Employment:

Keynes’ fundamental criticism of the quantity theory of money was based upon its unrealistic assumption of fall employment. Full employment is a rare phenomenon in the actual world. In a modern capitalist economy, less than full employment and not full employment is a normal feature. According to Keynes, as long as there is unemployment, every increase in money supply leads to a proportionate increase in output, thus leaving the price level unaffected.

4. Static Theory:

The quantity theory assumes that the values of V, V’, M’ and T remain constant. But, in reality, these variables do not remain constant. The assumption of constancy of these factors makes the theory a static theory and renders it inapplicable in the dynamic world.

5. Simple Truism:

The equation of exchange (MV = PT) is a mere truism and proves nothing. It is simply a factual statement which reveals that the amount of money paid in exchange for goods and services (MV) is equal to the market value of goods and services received (PT), or, in other words, the total money expenditure made by the buyers of commodities is equal to the total money receipts of the sellers of the commodities. The equation does not tell anything about the causal relationship between money and prices; it does not indicate which the cause is and which is the effect.

6. Technically Inconsistent:

Prof. Halm considers the equation of exchange as technically inconsistent. M in the equation is a stock concept; it refers to the stock of money at a point of time. V, on the other hand, is a flow concept, it refers to velocity of circulation of money over a period of time, M and V are non-comparable factors and cannot be multiplied together. Hence the left-hand side of the equation MV = PT is inconsistent.

7. Fails to Explain Trade Cycles:

The quantity theory does not explain the cyclical fluctuations in prices. It does not tell why during depression the prices fall even with the increase in the quantity of money and during the boom period the prices continue to rise at a faster rate in spite of the adoption of tight money and credit policy.

The proper explanation for the decline.in prices during depression is the fall in the velocity of money and for the rise in prices during boom period is the increase in the velocity of money. Thus, the quantity theory of money fails to explain the trade cycles. Crowther has remarked, “The quantity theory is at best, an imperfect guide to the causes of the cycle.”

8. Ignores Other Determinants of Price Level:

The quantity theory maintains that price level is determined by the factors included in the equation of exchange, i.e. by M, V and T, and unrealistically establishes a direct and proportionate relationship between the quantity of money and the price level. It ignores the importance of many other determinates of prices, such as income, expenditure, investment, saving, consumption, population, etc.

9. Fails to Integrate Monetary Theory with Price Theory:

The classical quantity theory falsely separates the theory of value from the theory of money. Money is considered neutral and changes in money supply are believed to affect the absolute prices and not relative prices. Keynes criticises this view and maintains that money plays an active role and both the theory of money and the theory of value are essential parts of the general theory of output, employment and money. He integrated the two theories through the rate of interest.

10. Money as a Store of Value Ignored:

The quantity theory of money considers money only as a medium of exchange and completely ignores its importance as a store of value. Keynes recognised the stores of value function of money and laid emphasis on the demand for money for speculative purpose as against the classical emphasis on the transactions and precautionary demand for money.

11. No Discussion of Velocity of Money:

The quantity theory of money does not discuss the concept of velocity of circulation of money, nor does it throw light on the factors influencing it. It regards the velocity of money to be constant and thus ignores the variation in the velocity of money which are bound to occur in the long period.

12. One-Sided Theory:

Fisher’s transactions approach is one- sided. It takes into consideration only the supply of money and its effects and assumes the demand for money to be constant. It ignores the role of demand for money in causing changes in the value of money.

13. No Direct and Proportionate Relation between M and P:

Keynes criticised the classical quantity theory of money on the ground that there is no direct and proportionate relationship between the quantity of money (M) and the price level (P). A change in the quantity of money influences prices indirectly through its effects on the rate of interest, investment and output.

The effect on prices is also not predictable and proportionate. It all depends upon the nature of the liquidity preference function, the investment function and the consumption function. The quantity theory does not explain the process of causation between M and P.

14. A Redundant Theory:

The critics regard the quantity theory as redundant and unnecessary. In fact, there is no need of a separate theory of money. Like all other commodities, the value of money is also determined by the forces of demand and supply of money. Thus, the general theory of value which explains the value determination of a commodity can also be extended to explain the value of money.

15. Crowther’s Criticism:

Prof. Crowther has criticised the quantity theory of money on the ground that it explains only ‘how it works’ of the fluctuations in the value of money and does not explain ‘why it works’ of these fluctuations. As he says, “The quantity theory can explain the ‘how it works’ of fluctuations in the value of money… but it cannot explain the ‘why it works’, except in the long period”.

Merits of Quantity Theory of Money:

Despite many drawbacks, the quantity theory of money has its merits:

1. Correct in Broader Sense:

It is true that in its strict mathematical sense (i.e., a change in money supply causes a direct and proportionate change in prices), the quantity theory may be wrong and has been rejected both theoretically and empirically. But, in the broader sense, the theory provides an important clue to the fluctuations in prices. Nobody can deny the fact that most of the changes in the prices of the commodities are due to changes in the quantity of money.

2. Validity of the Theory:

Till 1930s, the quantity theory of money was used by the economists and policy makers to explain the changes in the general price level and to form the basis of monetary policy. A number of historical instances like hyper- inflation in Germany in 1923-24 and in China in 1947-48 have proved the validity of the theory. In these cases large issues of money pushed up prices.

3. Basis of Monetary Policy:

The theory forms the basis of the monetary policy. Various instruments of credit control, like the bank rate and open market operations, presume that large supply of money leads to higher prices. Cheap money policy is advocated during depression to raise prices.

4. Revival of Quantity Theory:

In the recent times, the monetarists have revived the classical quantity theory of money. Milton Friedman, the leading monetarist, is of the view that the quantity theory was not given full chance to fight the great depression 1929-33; there should have been the expansion of credit or money or both.

He believes that the present inflationary rise in prices in most of the countries of the world is because of expansion of money supply much more than the expansion in real income. The proper monetary policy is to allow the money supply to grow in line with the growth in the country’s output.

Implications of Quantity Theory of Money:

Various theoretical and policy implications of the quantity theory of money are given below:

1. Proportionality of Money and Prices:

The quantity theory of money leads to the conclusion that the general level of prices varies directly and proportionately with the stock of money, i.e., for every percentage increase in the money stock, there will be an equal percentage increase in the price level. This is possible in an economy – (a) whose internal mechanism is capable of generating a full-employment level of output, and (b) in which individuals maintain a fixed ratio between their money holdings and money value of their transactions.

2. Neutrality of Money:

The quantity theory of money justifies the classical belief that money is neutral’ or ‘money is a veil’ or ‘money does not matter’. It implies that changes in the money supply are neutral in the sense that they affect the absolute prices and not the relative prices. Since, consumer spending and business spending decisions depend upon relative prices; changes in the money supply do not affect real variables such as employment and output. Thus, money is neutral.

3. Dichotomisation of the Price Process:

The quantity theory also justifies the dichotomisation of the price process by the classical economists into its real and monetary aspects. The relative (or real) prices are determined in the commodity markets and the absolute (or nominal) prices in the money market. Since money is neutral and changes in money supply affect only the monetary and not the real phenomena, the classical economists developed the theory of employment and output entirely in real terms and separated it from their monetary theory of absolute prices.

4. Monetary Theory of Prices:

The quantity theory of money upholds the view that the general level of prices is mainly a monetary phenomenon. The non-monetary factors, like taxes, prices of imported goods, industrial structure, etc., do not have lasting influence on the price level. These factors may raise the prices in the short run, but this price rise will reduce actual money balances below their desired level. This will lead to fall in money spending and a consequent fall in the price level until the original price is restored.

5. Role of Monetary Policy:

In a self-adjusting free-market economy in which changes in money supply do not affect the real macro variables of employment and output, there is little room left for a monetary policy. But the classical economists recognised the existence of frictional unemployment which represents temporary disequilibrium situation.

Such a situation arises when wages and prices are rigid downward. To me such a situation of unemployment, the classical economists advocated a stabilising monetary policy of increasing money supply. An increase in the money supply increases total spending and the general price level.

Wage will rise less rapidly (or relative wages will fall) in the labour surplus areas, thereby reducing unemployment Thus, through a judicious use of monetary policy, the time lag between disequilibrium and adjustment can shortened; or, in the case of frictional unemployment, the duration of unemployment can be reduce. Thus, the classical economists assigned a modest stabilising role to monetary policy to deal with the disequilibrium situation.

Related Articles

26.1 The Quantity Theory of Money

Learning Objectives

After you have read this section, you should be able to answer the following questions.

- What is the quantity theory of money?

- What is the classical dichotomy?

- According to the quantity theory, what determines the inflation rate in the long run?

We begin by presenting a framework to highlight the link between money growth and inflation over long periods of time.The framework complements our discussion of inflation in the short run, contained in Chapter 25 'Understanding the Fed'. The quantity theory of moneyA relationship among money, output, and prices that is used to study inflation. is a relationship among money, output, and prices that is used to study inflation. It is based on an accounting identity that can be traced back to the circular flow of income. Among other things, the circular flow tells us that

nominal spending = nominal gross domestic product (GDP).The “nominal spending” in this expression is carried out using money. While money consists of many different assets, you can—as a metaphor—think of money as consisting entirely of dollar bills. Nominal spending in the economy would then take the form of these dollar bills going from person to person. If there are not very many dollar bills relative to total nominal spending, then each bill must be involved in a large number of transactions.

The velocity of moneyNominal GDP divided by the money supply. is a measure of how rapidly (on average) these dollar bills change hands in the economy. It is calculated by dividing nominal spending by the money supply, which is the total stock of money in the economy:

If the velocity is high, then for each dollar, the economy produces a large amount of nominal GDP.

Using the fact that nominal GDP equals real GDP × the price level, we see that

And if we multiply both sides of this equation by the money supply, we get the quantity equationAn equation stating that the supply of money times the velocity of money equals nominal GDP., which is one of the most famous expressions in economics:

money supply × velocity of money = price level × real GDP.Quantity Theory Of Money Equation

Let us see how these equations work by looking at 2005. In that year, nominal GDP was about $13 trillion in the United States. The amount of money circulating in the economy was about $6.5 trillion.In Chapter 24 'Money: A User’s Guide', we discussed the fact that there is no simple single definition of money. This figure refers to a number called “M2,” which includes currency and also deposits in banks that are readily accessible for spending. If this money took the form of 6.5 trillion dollar bills changing hands for each transaction that we count in GDP, then, on average, each bill must have changed hands twice during the year (13/6.5 = 2). So the velocity of money was 2 in 2005.

Toolkit: Section 31.27 'The Circular Flow of Income'

You can review the circular flow of income in the toolkit.

The Classical Dichotomy

So far, we have just written a definition. There are two steps that take us from this definition to a theory of inflation. First we use the quantity equation to give us a theory of the price level. Then we examine the growth rate of the price level, which is the inflation rate.

In macroeconomics we are always careful to distinguish between nominal and real variables:

- Nominal variablesA variable defined and measured in terms of money. are defined and measured in terms of money. Examples include nominal GDP, the nominal wage, the dollar price of a carton of milk, the price level, and so forth. (Most nominal variables are measured in monetary units, but some are just numbers. For example, the nominal interest rate tells you how many dollars you will obtain next year for each dollar you invest in an asset this year. It is thus measured as “dollars per dollar,” so it is a number.)

- All variables not defined or measured in terms of money are real variablesA variable defined and measured in terms other than money, often in terms of real GDP.. They include all the variables that we divide by a price index in order to correct for the effects of inflation, such as real GDP, real consumption, the capital stock, the real wage, and so forth. For the sake of intuition, you can think of these variables as being measured in terms of units of (base year) GDP (so when we talk about real consumption, for example, you can think about the actual consumption of a bundle of goods and services by a household). Real variables also include the supply of labor (measured in hours) and many variables that have no specific units but are just numbers, such as the velocity of money or the capital-to-output ratio of an economy.

Prior to the Great Depression, the dominant view in economics was an economic theory called the classical dichotomyThe dichotomy that real variables are determined independently of nominal variables.. Although this term sounds imposing, the idea is not. According to the classical dichotomy, real variables are determined independently of nominal variables. In other words, if you take the long list of variables used by macroeconomists and write them in two columns—real variables on the left and nominal variables on the right—then you can figure out all the real variables without needing to know any of the nominal variables.

Following the Great Depression, economists turned instead to the aggregate expenditure modelThe relationship between planned spending and output. to better understand the fluctuations of the aggregate economy. In that framework, the classical dichotomy does not hold. Economists still believe the classical dichotomy is important, but today economists think that the classical dichotomy only applies in the long run.

The classical dichotomy can be seen from the following thought experiment. Start with a situation in which the economy is in equilibrium, meaning that supply and demand are in balance in all the different markets in the economy. The classical dichotomy tells us that this equilibrium determines relative prices (the price of one good in terms of another), not absolute prices. We can understand this result by thinking about the markets for labor, goods, and credit.

Figure 26.2 'Labor Market Equilibrium' presents the labor market equilibrium. On the vertical axis is the real wage because households and firms make their labor supply and demand decisions based on real, not nominal, wages. Households want to know how much additional consumption they can get by working more, whereas firms want to know the cost of hiring more labor in terms of output. In both cases, it is the real wage that determines economic choices.

Now think about the markets for goods and services. The demand for any good or service depends on the real income of households and the real price of the good or service. We can calculate real prices by correcting for inflation: that is, by dividing each nominal price by the aggregate price level. Household demand decisions depend on real variables, such as real income and relative prices.If you have studied the principles of microeconomics, remember that the budget constraint of a household depends on income divided by the price of one good and on the price of one good in terms of another. If there are multiple goods, the budget constraint can be determined by dividing income by the price level and by dividing all prices by the same price level. The same is true for the supply decisions of firms. We have already argued that labor demand depends on only the real wage. Hence the supply of output also depends on the real, not the nominal, wage. More generally, if the firm uses other inputs in the production process, what matters to the firm’s decision is the price of these inputs relative to the price of its output, or—more generally—relative to the overall price level.If you have studied the principles of microeconomics, the condition that price equals marginal cost is used to characterize the output decision of a firm. What matters then is the price of the input, relative to the price of output.

What about credit markets? The supply and demand for credit depends on the real interest rate. This means that those supplying credit think about the return they receive on making loans in real terms: although the loan may be stated in terms of money, the supply of credit actually depends on the real return. The same is true for borrowers: a loan contract may stipulate a nominal interest rate, but the real interest rate determines the cost of borrowing in terms of goods. The supply of and demand for credit is illustrated in Figure 26.3 'Credit Market Equilibrium'.

Figure 26.3 Credit Market Equilibrium

The credit market equilibrium occurs at a quantity of credit extended (loans) and a real interest rate where the quantity supplied is equal to the quantity demanded.

Toolkit: Section 31.3 'The Labor Market', Section 31.24 'The Credit (Loan) Market (Macro)', and Section 31.8 'Correcting for Inflation'

You can review the labor market and the credit market, together with the underlying demand and supply curves, in the toolkit. You can also review how to correct for inflation.

The classical dichotomy has a key implication that we can study through a comparative statics exercise. Recall that in a comparative statics exercise we examine how the equilibrium prices and output change when something else, outside of the market, changes. Here we ask: what happens to real GDP and the long-run price level when the money supply changes? To find the answer, we begin with the quantity equation:

money supply × velocity of money = price level × real GDP.Previously we discussed this equation as an identity—something that must be true by the definition of the variables. Now we turn it into a theory. To do so, we make the assumption that the velocity of money is fixed. This means that any increase in the money supply must increase the left-hand side of the quantity equation. When the left-hand side of the quantity equation increases, then, for any given level of output, the price level is higher (equivalently, for any given value of the price level, the level of real GDP is higher).

What then changes when we change the money supply: output, prices, or both? Based on the classical dichotomy, we know the answer. Real variables, such as real GDP and the velocity of money, stay constant. A change in a nominal variable—the money supply—leads to changes in other nominal variables, but real variables do not change. The fact that changes in the money supply have no long-run effect on real variables is called the long-run neutrality of moneyThe fact that changes in the money supply have no long-run effect on real variables..

Toolkit: Section 31.16 'Comparative Statics'

You can find more details on how to conduct comparative static exercises in the toolkit.

How does this view of the effects of monetary policy fit with the monetary transmission mechanismA mechanism explaining how the actions of a central bank affect aggregate economic variables, in particular real GDP.?See Chapter 25 'Understanding the Fed'. The monetary transmission mechanism explains that the monetary authority affects aggregate spending by changing its target interest rate.

- The monetary authority changes interest rates.

- Changes in interest rates influence spending on durables by firms and households.

- Changes in spending influence aggregate spending through a multiplier effect.

Remember that the monetary authority changes interest rates through open-market operations. If it wants to boost aggregate spending, it does so by cutting interest rates, and it cuts interest rates by purchasing government bonds with money. An interest rate cut is equivalent to an increase in the supply of money, so the monetary transmission mechanism also teaches us that an increase in the supply of money leads to an increase in aggregate spending.There is one difference, unimportant here, which is that the monetary transmission mechanism does not necessarily suppose that the velocity of money is constant. The monetary transmission mechanism is useful when we want to understand the short-run effects of monetary policy. When studying the long run, it is easier to work with the quantity equation and to think about monetary policy in terms of the supply of money rather than interest rates.

Finally, a reminder: in the short run, the neutrality of money does not hold. This is because in the short run we assume stickiness of nominal wages and/or prices. In this case, changes in the nominal money supply will lead to changes in the real money supply. With sticky wages and/or prices, the classical dichotomy is broken.

Long-Run Inflation

We now use the quantity equation to provide us with a theory of long-run inflation. To do so, we use the rules of growth rates. One of these rules is as follows: if you have two variables, x and y, then the growth rate of the product (x × y) is the sum of the growth rate of x and the growth rate of y. We can apply this to the quantity equation:

money supply × velocity of money = price level × real GDP.Simple Quantity Theory Of Money

The left side of this equation is the product of two variables, the money supply and the velocity of money. The right side is likewise the product of two variables. So we obtain

growth rate of the money supply + growth rate of the velocity of money= inflation rate + growth rate of output.We have used the fact that the growth rate of the price level is, by definition, the inflation rate.

Toolkit: Section 31.21 'Growth Rates'

You can review the rules of growth rates in the toolkit.

We continue to assume that the velocity of money is a constant.In fact, the velocity of money might also grow over time as a result of developments in the financial sector. Saying that the velocity of money is constant is the same as saying that its growth rate is zero. Using this fact and rearranging the equation, we discover that the long-run inflation rate depends on the difference between how rapidly the money supply grows and how rapidly output grows:

inflation rate = growth rate of money supply − growth rate of output.The long-run growth rate of output does not depend on the growth rate of the money supply or the inflation rate. We know this because long-run output growth depends on the accumulation of capital, labor, and technology. From our discussion of labor and credit markets, equilibrium in these markets is described by real variables. Equilibrium in the labor market depends on the real wage and not on any nominal variables. Likewise, equilibrium in the credit market tells us that the level of investment does not depend on nominal variables. Since the capital stock in any period is just the accumulation of past investment, we know that the stock of capital is also independent of nominal variables.

The Quantity Theory Of Money Assumes That Real Gdp Is Defined

Therefore there is a direct link between the money supply growth rate and the inflation rate. The classical dichotomy teaches us that changes in the money supply do not affect the velocity of money or the level of output. It follows that any changes in the growth rate of the money supply will show up one-for-one as changes in the inflation rate. We say more about monetary policy later, but notice that there are immediate implications for the conduct of monetary policy:

- In a growing economy, there are more transactions taking place, so there is typically a need for more money to facilitate those transactions. Thus some growth of the money supply is probably desirable to match the increased income.

- If the monetary authorities want a stable price level—zero inflation—in the long run, then they should try to set the growth rate of the money supply equal to the (long-run) growth rate of output.

- If the monetary authorities want a low level of inflation in the long run, then they should aim to have the money supply grow just a little bit faster than the growth rate of output.

Keep in mind that this is just a theory. The quantity equation holds as an identity. But the assumption of constant velocity and the statement that long-run output growth is independent of money growth are assertions based on a body of theory. We now look at how well this theory fits the facts.

Key Takeaways

- The quantity theory of money states that the supply of money times the velocity of money equals nominal GDP.

- According to the classical dichotomy, real variables, such as real GDP, consumption, investment, the real wage, and the real interest rate, are determined independently of nominal variables, such as the money supply.

- Using the quantity equation along with the classical dichotomy, in the long run the inflation rate equals the rate of money growth minus the growth rate of output.

Quantity Theory Of Money Definition

Checking Your Understanding

Quantity Theory Of Money Assumptions

- Is the real wage a nominal variable? What about the money supply?

- If velocity of money decreases by 2 percent and the money supply does not grow, can you say what will happen to nominal GDP growth? Can you say what will happen to inflation?