- Money Supply Real Exchange Rates

- Money Supply Real Exchange Rate Equation

- Real Exchange Rate Formula

- Money Supply Real Exchange Rate Equation

- Nominal Interest Rate

As the first step in extending the PPP theory, we define the concept of a real exchange rate. The real exchange rate between two countries' currencies is a broad summary measure of the prices of one country's goods and services relative to the other's. It is natural to introduce the real exchange rate concept at this point because the major prediction of PPP is that real exchange rates never change, at least not permanently. To extend our model so that it describes the world more accurately, we need to examine systematically the forces that can cause dramatic and permanent changes in real exchange rates.

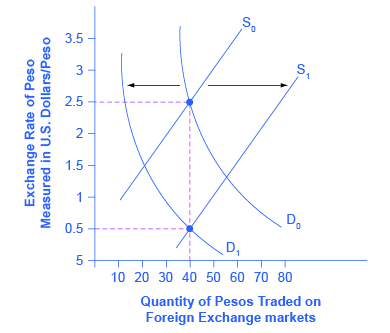

Monetary policy, increasing domestic money supply reduces the interest rate, and when the other conditions are constant, the outflow of capital occurs. Capital outflow reduces the supply of currency and increases the exchange rate. If the current system is a fixed exchange rate regime, the central bank.

- Figure 25.12 An Increase in the Money Supply. The Fed increases the money supply by buying bonds, increasing the demand for bonds in Panel (a) from D 1 to D 2 and the price of bonds to P b 2. This corresponds to an increase in the money supply to M′ in Panel (b). The interest rate must fall to r 2 to achieve equilibrium.

- Exchange Market (cont.) Aggregate real money demand, L(R,Y) Interest rate, R Real money holdings Aggregate real money supply MS P R1 Aggregate real money demand, L (R, Y) Interest rate, R Real money holdings Aggregate real money supply M S P R 1.

'This argument assumes that factor endowment differences between rich and poor countries are sufficiently great that factor-price equalization cannot hold.

STICKY PRICES AND THE LAW OF ONE PRICE: EVIDENCE FROM SCANDINAVIAN DUTY-FREE SHOPS

Sticky nominal prices and wages are central to macroeconomic theories, but just why might it be difficult for money prices to change from day to day as market conditions change? One reason is based on the idea of 'menu costs.' Menu costs could arise from several factors, such as the actual costs of printing new price lists and catalogs. In addition, firms may perceive a different type of menu cost due to their cutsomers' imperfect information about competitors' prices. When a firm raises its price, some customers will shop around elsewhere and find it convenient to remain with a competing seller even if all sellers have raised their prices. In the presence of these various types of menu cost, sellers will often hold price constant after a change in market conditions until they are certain the change is permanent enough to make incurring the costs of price change worthwhile.*

If there were truly no barriers between two markets with goods priced in different currencies, sticky prices would be unable to survive in the face of an exchange rate change. All buyers would simply flock to the market where a good had become cheapest. But when some trade impediments exist, deviations from the law of one price do not induce unlimited arbitrage, so it is feasible for sellers to hold prices constant despite exchange rate changes. In the real world, trade barriers appear to be significant, widespread, and often subtle in nature.

Apparently, arbitrage between two markets may be limited even when the physical distance between them is zero, as a surprising study of pricing behavior in Scandinavian duty-free outlets shows, Swedish economists Marcus Asplund and Richard Friberg studied pricing behavior in the duty-free stores of two Scandinavian ferry lines and the airline SAS, all of whose catalogs quote the prices of each good in several currencies for the convenience of customers from different coun-tries.f Since it is costly to print the catalogs, they are reissued only from time to time with revised prices. In the interim, however, fluctuations in exchange rates induce multiple, changing prices for the same good. For example, on the Birka Line of ferries between Sweden and Finland, prices

*It is when economic conditions are very volatile that prices seem to become most flexible. For example, restaurant menus will typically price their catch of the day at 'market' so that the price charged (and the fish offered) can reflect the high variability in fishing outcomes.

t'The Law of One Price in Scandinavian Duty-Free Stores,' American Economic Review 91 (September 2001), pp. 1072-1083.

As we will see, real exchange rates are important not only for quantifying deviations from PPP but also for analyzing macroeconomic demand and supply conditions in open economies. When we wish to differentiate a real exchange rate, which is the relative price of two output baskets, from a relative price of two currencies, we will refer to the latter as a nominal exchange rate. But when there is no risk of confusion we will continue to use the shorter term exchange rate to cover nominal exchange rates.

Money Supply Real Exchange Rates

Real exchange rates are defined, however, in terms of nominal exchange rates and price levels. So before we can give a more precise definition of real exchange rates, we need to clarify the price level measure we will be using. Let Pus, as usual, be the price level in the United States, and Py the price level in Europe. Since we will not be assuming absolute PPP (as we did in our discussion of the monetary approach), we no longer assume the price level can be measured by the same basket of commodities in the United States as in Europe. Because we will soon want to link our analysis to monetary factors, we require instead that were listed in both Finnish markka and Swedish kronor between 1975 and 1998, implying that a relative depreciation of the markka would make it cheaper to buy cigarettes or vodka by paying markka rather than kronor.

Despite such price discrepancies, Birka Line was always able to do business in both currencies—passengers did not rush to buy at the lowest price. Swedish passengers, who held relatively large quantities of their own national currency, tended to buy at the kronor prices, whereas Finnish customers tended to buy at markka prices. Often, Birka Line would take advantage of publishing a new catalog to reduce deviations from the law of one price. The average deviation from the law of one price in the month just before such a price adjustment was 7.21 percent, but only 2.22 percent in the month of a price adjustment. One big impediment to taking advantage of the arbitrage opportunities was the cost of changing currencies at the onboard foreign exchange booth— roughly 7.5 percent. That transaction cost, given different passengers' currency preference at the time of embarkation, acted as an effective trade barrier, t

Surprisingly, Birka Line did not completely eliminate law-of-one-price deviations when it changed catalog prices. Instead, Birka Line practiced a kind of pricing to market on its ferries. Usually, exporters who price to market discriminate between different consumers based on their different locations, but Birka was able to discriminate based on different nationality and currency preference, even with all potential consumers located on the same ferry boat.

The1 idea that currency preference, exchange costs, and calculation costs create fixed transaction cost bands within which price differentials can persist receives further support from Asplund and Friberg's data on SAS in-flight duty-free catalogs. SAS also practiced pricing to market, but with smaller planned deviations from the law of one price for more expensive items (for example, the $138 Mont Blanc pen). For a given percentage price discrepancy, the gains to purchasing at the lowest price are greater the more expensive the item. The finding that SAS had more latitude for pricing to market with low-cost items is therefore consistent with the presence of fixed barriers to arbitrage.

^Customers could pay in the currency of their choice not only with cash, but also with credit cards, which involve much lower foreign exchange conversion fees but convert at an exchange rate prevailing a few days after the purchase of the goods. Asplund and Friberg hypothesize that for such small purchases, uncertainty and the costs of calculating relative prices (in addition to the credit-card exchange fees) might have been a sufficient deterrent to transacting in a relatively unfamiliar currency.

each country's price index give a good representation of the purchases that motivate its residents to demand its money supply.

No measure of the price level does this perfectly, but we must settle on some definition before the real exchange rate can be defined formally. To be concrete, you can think of Pvs as the dollar price of an unchanging basket containing the typical weekly purchases of U.S. households and firms; PE, similarly, is based on an unchanging basket reflecting the typical weekly purchases of European households and firms. The point to remember is that the United States price level will place a relatively heavy weight on commodities produced and consumed in America, the European price level a relatively heavy weight on commodities produced and consumed in Europe.17

l7A similar presumption was made in our discussion of the transfer problem in Chapter 5. As we observed in that chapter, nontradables are one important factor behind the relative preference for home products.

Having described the reference commodity baskets used to measure price levels, we can now formally define the real dollar/euro exchange rate, denoted q$f£, as the dollar price of the European basket relative to that of the American. We can express the real exchange rate as the dollar value of Europe's price level divided by the U.S. price level or, in symbols, as

<?$/€ = * WjS- (IS'6>

A numerical example will clarify the concept of the real exchange rate. Imagine that the European reference commodity basket costs €100 (so that PE = €100 per European basket), that the U.S. basket costs $120 (so that Pvs = $120 per U.S. basket), and that the nominal exchange rate is Em = $1.20 per euro. The real dollar/euro exchange rate would then be

_ ($ 1.20 per euro) X (€100 per European basket) Qm ($120 per U.S. basket)

= ($120 per European basket)/($120 per U.S. basket)

= 1 U.S. basket per European basket.

A rise in the real dollar/euro exchange rate qm, (which we call a real depreciation of the dollar against the euro) can be thought of in several equivalent ways. Most obviously, (15-6) shows this change to be a fall in the purchasing power of a dollar within Europe's borders relative to its purchasing power within the United States. This change in relative purchasing power occurs because the dollar prices of European goods (Eye X PE ) rise relative to those of U.S. goods (Pvs).

In terms of our numerical example, a 10 percent nominal dollar depreciation, to = $1.32 per euro, causes qy£ to rise to 1.1 U.S. baskets per European basket, a real dollar depreciation of 10 percent against the euro. (The same change in q$/f could result from a 10 percent rise in PE or a 10 percent fall in Pus.) The real depreciation means that the dollar's purchasing power over European goods and services falls by 10 percent relative to its purchasing power over U.S. goods and services.

Money Supply Real Exchange Rate Equation

Alternatively, even though many of the items entering national price levels are nontraded, it is useful to think of the real exchange rate as the relative price of European products in general in terms of American products, that is, the price at which hypothetical trades of American for European commodity baskets would occur if trades at domestic prices were possible. The dollar is considered to depreciate in real terms against the euro when q%m rises because the hypothetical purchasing power of America's products in general over Europe's declines. America's goods and services become cheaper relative to Europe's.

Real Exchange Rate Formula

Money Supply Real Exchange Rate Equation

A real appreciation of the dollar against the euro is a fall in qm. This fall indicates a decrease in the relative price of products purchased in Europe, or a rise in the dollar's European purchasing power compared with that in the United States.18

'Since E(/$ — l/£j,f, so that qiJ( — PEi{Ef/} x Pvs) = 1 tq€/s, a real depreciation of the dollar against the euro is the same as a real appreciation of the euro against the dollar (that is, a rise in the purchasing power of the euro within the United States relative to its purchasing power within Europe, or a fall in the relative price of American products in terms of European products).

Our convention for describing real depreciations and appreciations of the dollar against the euro is the same one we use for nominal exchange rates (that is, Ey€ up is a dollar depreciation, E^ down an appreciation). Equation (15-6) shows that at unchanged output prices, nominal depreciation (appreciation) implies real depreciation (appreciation). Our discussion of real exchange rate changes thus includes, as a special case, an observation we made in Chapter 13: With the domestic money prices of goods held constant, a nominal dollar depreciation makes U.S. goods cheaper compared with foreign goods, while a nominal dollar appreciation makes them more expensive.

Equation (15-6) makes it easy to see why the real exchange rate can never change when relative PPP holds. Under relative PPP, a 10 percent rise in Ei/f_, for instance, would always be exactly offset by a 10 percent fall in the price level ratio leaving qm unchanged.

Continue reading here: Demand Supply and the Long Run Real Exchange Rate

Nominal Interest Rate

Was this article helpful?